Minutes of a witness testimony1

[Read the original testimony in Polish here.]

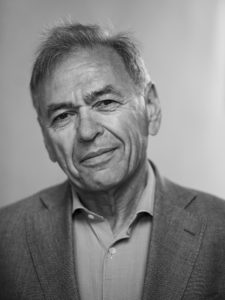

Dr. Salomon Hirschberg, attorney, born in Tarnopol on 30 April 1903, son of Dawid and Fryderyka née Goliger, living in Katowice at Mickiewicza Street No. 2, Flat 4.

Recorded by Natan Szternfinkiel, MA

The Germans entered Tarnopol on Wednesday 2 July 1941. For the first two days after their entry they kept a low profile and there was no talk of anti-Jewish incidents.

On 4 July 1941 at about 10 o’clock in the morning gunfire was heard and, at the same time, I heard a terrifying rumble. Together with all the other men in our family I went into our hiding place; only the women stayed home2. During this and the following days the SS, the soldiers of the Wehrmacht, and Ukrainians with yellow and blue armbands turned up several times looking for men. According to what I have heard, a council was held on 3 July 1941 by the German military authorities with the participation of local Ukrainians, at which they decided to avenge the deaths of prisoners at the Tarnopol prison.

From the early morning hours of 3 July 1941, crowds of local people arrived at the prison to see the remains of some twenty prisoners. There were two Jews among those prisoners but, notwithstanding, locals spread rumours that “the perpetrators were Jews, all of them communists”. I learned later that some Jews had been forewarned by their Ukrainian friends that repressions against Jews were expected to start on 4 July 1941.

On 4 July at 10 o’clock in the morning a pogrom started in Tarnopol. Simultaneously in almost all streets, especially in those inhabited by the Jewish population, Germans and Ukrainians started shooting at Jewish passers-by and at those who tried to save themselves by escaping. They entered houses and pulled Jews out of their homes. Some of the Jews were led to the prison and ordered to excavate cellars in search of human skeletons. Ukrainians and Germans stood above the digging Jews and hit them with rifle butts and iron crowbars. The Jews had to work without rest, water, or food. Anybody who paused for a moment was massacred to death. Following German orders, the Jews had to carry the dead bodies into the prison courtyard and heap them in a pile. Simultaneously, the Germans and Ukrainians brought into the courtyard groups of Jews from the city and shot them on the spot immediately upon arrival.

A certain Hołejko, aged over forty, former clerk at the Social Security Office and later Chief Bookkeeper at the Oblzdrav (The Regional Health Department in Tarnopol), was now the commandant of the Ukrainian police that conducted this pogrom together with the Germans. The deputy commandant of the police was a legal apprentice whose name I do not recall today, a son-in-law of Dr Dymitr Ładyka who was an attorney and former member of the parliament of the Polish Republic. Immediately before the outbreak of war in 1941 Dymitr Ładyka gave a speech that was broadcast from Kraków as far as I remember, urging the murder of Jews.3

At the same time, the Germans and Ukrainians led groups of Jews to Majka’s house at Baron Hirsch Street and Rynek (formerly the Garfein School) and shot them systematically inside the house. Jews were also led out of their homes and shot in nearby courtyards and squares.

The Ukrainians who took part in the pogrom were from among the local population and also from the nearby villages. Those who pulled the Jews out of their homes were assisted by local inhabitants who pointed out Jewish homes and hiding places.

On 4 July 1941, on the first day of the pogrom, a very large number of Jews were murdered. However, a Ukrainian whose name I presently do not recall intervened with the German authorities and in the evening, those Jews whom the executioners had not murdered as yet were released from prison.

On 5 July the pogrom continued in the same manner. In the evening of 5 July the Germans and Ukrainians led the surviving Jews from the prison to the building of the Municipal Communal Savings Bank at Sobieski Square, where they lined them up and ordered them to stand at attention the whole night. Anybody who moved was murdered in an atrocious manner, and finished off with crowbars and butt ends. The victims were frequently shot. Among the victims was my nephew Marceli Saphir, a student at the Institute of Technology. He was caught the previous day for “work” in prison but released in the evening; he told my sister what transpired at the prison. The next day he was caught again and never came back.4

On the third day of the pogrom, that is on 6 July 1941, the Germans started organizing a so called Nationalrat, engaging to this end Marek Gottfried, headmaster of the Perl School. People said that once the Nationalrat has been established, it would become the intermediary between the Jewish population and the Germans, and the pogrom would come to an end. According to German instructions, the Nationalrat was to consist of a hundred (100) persons. A candidate list of members of the local working intelligentsia was composed by Gottfried, complete with their given names, surnames and addresses, in accordance with the instructions issued by the Germans.

The Germans visited each person on the Gottfried list in order to recruit them to the Nationalrat. Several people joined voluntarily, assuming that participation in the Nationalrat would guarantee their safety. However, the majority of people on the list were either hiding or dead, and so the Germans filled the quota with other Jews caught for work.

Already on 6 July 1941 the Germans would also pick up Jews for various work assignments; some of these groups were brought to the new Gestapo headquarters in the building at 11 Listopada Street.5 There, a selection was made and members of the intelligentsia were separated from the workers, while those with knowledge of the German language were designated for the Nationalrat, loaded onto trucks by the Gestapo and the SS, and taken to the vicinity of the brick factory on Tarnowski Street. A few weeks later, permission was obtained to excavate the remains of several dozen members of the so called Nationalrat who were murdered there.6 Most of them had been buried alive as indicated by the following evidence: the body of my cousin Izydor Hirschberg, an engineer, after exhumation did not bear any marks of having been shot, while the shape of his mouth suggested suffocation.7 Dr Salomon Horowitz, a lawyer in Tarnopol, had been buried in an upright position holding a shovel in his hand.8 Numerous other people showed signs of suffocation. Most Nationalrat members murdered there were members of the intelligentsia. Among those was another cousin of mine, Eliasz Hirschberg, a student at the Institute of Technology.9

A few Nationalrat members were spared; the Germans released them “due to old age”. Among those released was Gottfried who had authored the list, the teacher Kapan10, and Luft; they were released by the Germans from the assembly at the Gestapo quarters. Another Jew, from Berlin, was released from the site of execution on the grounds of being from Germany. He is the source of the above information. He was not willing to provide any details, claiming that the acts of murder had been so atrocious that he was not able to talk about them. The Germans brought in the members of the Nationalrat and murdered them on 7 July 1941.

Round-ups continued on 8 July 1941, mostly from the prison where Jews were murdered in the same manner as described above. On 9 July 1941, I saw out of the window of my flat several carts loaded with dead bodies, heading in the direction of the cemetery. Jews with shovels walked close to each cart while Germans and Ukrainians formed their escort. Some of the carts were taken to the old Jewish cemetery, the rest to the new Jewish cemetery. During the burial the executioners murdered almost all those who were engaged in burying their brethren. Most of those Jews were not even shot; they were finished off with iron crowbars and rifle butts.

About two weeks later, the remains of the Jews buried in the old Jewish cemetery were partially exhumed. Some twenty bodies were exhumed, moved to the new Jewish cemetery and buried there.11 The exhumation process was interrupted on German orders because, as it happened, some errant officers had turned up in Tarnopol; having taken interest in these activities, they photographed the dead bodies, the mass graves, and the assembled families.

On 10 July 1941 the Germans and Ukrainians led about 60–70 people to the Jewish cemetery and murdered them there. Among those murdered were Max Faden12, Herman Bielfeld13, Rosenfeld the son of Mojżesz Lejb Rosenfeld14, and others.

On 11 July I was caught by a Ukrainian who turned me over to the hands of a German together with a group of other Jews. The German then led us to close to the prison and ordered us to wait. Once he was some distance away, I took a chance and escaped. He caught me though, and shot at me, but missed for some reason. He led me to the Town Hall courtyard where Jews were at work. I worked all day long, too. The German tormented me, ordered me to clean lavatories with my bare hands, to carry 100 kg packs and to clean shoes, in order to humiliate me.

I was released in the evening but unfortunately I was caught by the SS on my way home and transported along with a group of other Jews to the old Catholic cemetery. There, by whatever means we had – and in my case with bare hands – we were to dig a grave for the bodies of Soviet soldiers that lay there. Finally, I was released to go home. During the work the SS men beat us with whatever turned up, kicked us, not allowing us to catch our breath even for a moment.

Casualties of the pogrom were recorded by the Ukrainian Health Department based on reports by Jewish families. The number of recorded deaths exceeded 4 000 (four thousand) people.15 Such was the effect of the pogrom that went on in Tarnopol between 4 and 10 July 1941. There continued to be casualties among the Jewish population almost daily for a long time after 10 July 1941.

Recorded by Szternfinkiel,

Katowice, 20 July 1948

Translated from the Polish and annotated by Jurek Hirschberg

Read the original testimony in Polish here.

See the translator’s comments here.

Notes

- Testimonies of Surviving Jews. Recorded on 20 July 1948. Hirschberg Salomon. Original 10 pages manuscript in Polish, 6 pages typed copy. The ŻIH (Jewish Historical Institute) Archive. Signature 301/3774. Film No. N 0757. ↵

- The family had lived since 1911 in their house at Szeptyckich 4. ↵

- Dymitr Ładyka (1889–1945) was a Tarnopol lawyer, a Ukrainian politician during the interwar period, and member of the Polish parliament 1928–1935. He moved to Germany at the end of the war and died in the bombing of Dresden. Biblioteka Sejmowa, bs.sejm.gov.pl, entry 885. ↵

- Marceli Saphir (1920–1941) was the son of Salomon Hirschberg’s sister Fryderyka (1891–1943) and her husband Hermann Saphir (1887–1938), an engineer in Tarnopol. ↵

- The Gestapo headquarters in Tarnopol were situated at Listopada Street – the former 29 Listopada Street. ↵

- The Central State Historical Archives of Ukraine in Lviv have in their holdings part of the preserved vital records of the Jewish community of Tarnopol, including a partial list of death records between 4 July 1941 and 30 August 1942. Among those records, 349 refer to deaths dated between 4 and 10 July 1941. Films of these records are in the collection of the Genealogical Society of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah. GSU: microfilm # 2405431, batch # 3. According to those records 19 bodies of those murdered on 7 July 1941 were examined on 14 August and additional 18 on 18 August 1941. GSU No. 204–222, 224–241. ↵

- Izydor Hirschberg, residing at Tarnowskiego 23, aged 35, male, married, died on 7 July 1941 due to sudden death. The remains were inspected on 15 August 1941. GSU No. 205. Izydor Hirschberg (1906–1941) was the son of Salomon Hirschberg’s cousin Jakob Scharje Hirschberg (1874–?) and his wife Rebeka née Barbasch (1876–?). ↵

- Salomon Horowitz, residing at 3 Maja 2, aged 49, male, married, died on 7 July 1941 due to sudden death. The remains were inspected on 15 August 1941. GSU No. 212. ↵

- Eljasz Hirschberg, residing at Brücknera 12, aged 20, male, single, died on 7 July 1941 due to sudden death. The remains were inspected on 15 August 1941. GSU No. 211. Eliasz (Elijahu) Hirschberg (1922–1941) was the son of Jakob Scharje’s brother Chaim Hirschberg (1888–1943) and his wife Ester (1898–1943). ↵

- Kapan the religion teacher was shot by Herman Müller on 18 April 1943. Testimonies of Surviving Jews. Żaneta Sas. The ŻIH (Jewish Historical Institute) Archive. Signature 301/4196. ↵

- 18 bodies of those killed in the first days of the pogrom were examined on 21 July, 33 bodies on 23 July and 45 bodies on 25 July 1941. The remains of those exhumed in the old Jewish cemetery may have been among them. GSU No. 75–92, 95–127, 128–173. ↵

- Max Faden, residing at Podhoreckiego, aged 37, male, single, died on 7 July 1941 due to sudden death. The remains were inspected on 9 September 1941. GSU No. 270. ↵

- Herman Bielfeld, residing at Kotlerewskiego 26, aged 39, male, single, died on 7 July 1941 due to sudden death. The remains were inspected on 9 September 1941. GSU No. 268. ↵

- Wolf Rosenfeld, residing at Kotlerewskiego 26, aged 27, male, single, died on 7 July 1941 due to sudden death. The remains were inspected on 9 September 1941. GSU No. 269. He was probably the son of Mojżesz Lejb Rosenfeld. ↵

- This register was apparently unrelated to GSU. ↵